From An official of the United States government

The Words of a Killer

No two people write alike.

Media www.rajawalisiber.com – It was something Terry Turchie, the lead FBI agent on the UNABOM Task Force, remembered a creative writing teacher saying to him in school. Although that advice came many years before Turchie was investigating a serial bomber, it would prove crucial to solving the case.

The Unabomber began his campaign of violence with a package bomb he left in a parking lot of the University of Illinois’ Chicago Circle Campus in 1978. He would go on to place a bomb on an aircraft and leave others in university buildings and by computer stores. He would also mail powerful bombs to a number of university professors and to businesses and executives. He unleashed 16 bombs that killed three people and injured nearly two dozen before he was arrested on April 3, 1996.

Despite being active for nearly 20 years, the Unabomber was meticulous about leaving no evidence that could be traced to him and took pains to avoid being seen.

“He was the most careful serial bomber anyone had ever seen,” said Special Agent Kathleen Puckett, who worked on the UNABOM task force and led efforts to profile the bomber. (Both Puckett and Turchie are now retired from the FBI.)

But when the bomber began communicating, first in letters to some of his victims and then with the media, Turchie said he was also inadvertently communicating with the FBI. Investigators were analyzing his every word.

“We didn’t have any line to him except the letters he started sending in 1993,” said Puckett. “It was a bonanza of information.” The letters pointed investigators to ideas he held, topics he studied, and books that were meaningful to him. To Puckett, who was working toward her Ph.D. in clinical psychology, they revealed things about his education, age, and personality.

After lethal bombings in 1994 and 1995, the Unabomber wrote to several publications asking them to publish an essay that he believed would memorialize his achievements and his ideology. Although the bomber promised to cease his bombs if his writings were published, FBI leaders pushed for publication with a different goal in mind: using the Unabomber’s own words to identify him.

“Somebody would recognize this,” Turchie said of the decision. “The writings were very passionate—that there’s no question this man really believes in what he’s writing here. So he probably held these beliefs his entire life.”

How do you catch a twisted genius who aspires to be the perfect, anonymous killer—who builds untraceable bombs and delivers them to random targets, who leaves false clues to throw off authorities, who lives like a recluse in the mountains of Montana and tells no one of his secret crimes?

That was the challenge facing the FBI and its investigative partners, who spent nearly two decades hunting down this ultimate lone wolf bomber.

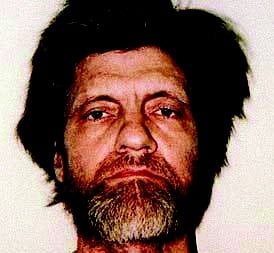

The man that the world would eventually know as Theodore Kaczynski came to our attention in 1978 with the explosion of his first, primitive homemade bomb at a Chicago university. Over the next 17 years, he mailed or hand delivered a series of increasingly sophisticated bombs that killed three Americans and injured nearly two dozen more. Along the way, he sowed fear and panic, even threatening to blow up airliners in flight.

In 1979, an FBI-led task force that included the ATF and U.S. Postal Inspection Service was formed to investigate the “UNABOM” case, code-named for the UNiversity and Airline BOMbing targets involved. The task force would grow to more than 150 full-time investigators, analysts, and others. In search of clues, the team made every possible forensic examination of recovered bomb components and studied the lives of victims in minute detail. These efforts proved of little use in identifying the bomber, who took pains to leave no forensic evidence, building his bombs essentially from “scrap” materials available almost anywhere. And the victims, investigators later learned, were chosen randomly from library research.

We felt confident that the Unabomber had been raised in Chicago and later lived in the Salt Lake City and San Francisco areas. This turned out to be true. His occupation proved more elusive, with theories ranging from aircraft mechanic to scientist. Even the gender was not certain: although investigators believed the bomber was most likely male, they also investigated several female suspects.

The big break in the case came in 1995. The Unabomber sent us a 35,000 word essay claiming to explain his motives and views of the ills of modern society. After much debate about the wisdom of “giving in to terrorists,” FBI Director Louis Freeh and Attorney General Janet Reno approved the task force’s recommendation to publish the essay in hopes that a reader could identify the author.

After the manifesto appeared in The Washington Post, thousands of people suggested possible suspects. One stood out: David Kaczynski described his troubled brother Ted, who had grown up in Chicago, taught at the University of California at Berkeley (where two of the bombs had been placed), then lived for a time in Salt Lake City before settling permanently into the primitive 10’ x 14’ cabin that the brothers had constructed near Lincoln, Montana.

Most importantly, David provided letters and documents written by his brother. Our linguistic analysis determined that the author of those papers and the manifesto were almost certainly the same. When combined with facts gleaned from the bombings and Kaczynski’s life, that analysis provided the basis for a search warrant.

On April 3, 1996, investigators arrested Kaczynski and combed his cabin. There, they found a wealth of bomb components; 40,000 handwritten journal pages that included bomb-making experiments and descriptions of Unabomber crimes; and one live bomb, ready for mailing.

Kaczynski’s reign of terror was over. His new home, following his guilty plea in January 1998: an isolated cell in a “Supermax” prison in Colorado.

Timeline of Unabomber Devices

- May 25, 1978: A passerby found a package, addressed and stamped, in a parking lot at the University of Illinois, Chicago Circle Campus. The package was returned to the person listed on the return address, Northwestern University Professor Buckley Crist, Jr. He did not recognize the package and called campus security. The package exploded upon opening and injured the security officer.

- May 9, 1979: A graduate student at Northwestern University is injured when he opened a box that looked like a present. It had been left in a room used by graduate students.

- November 15, 1979: American Airlines Flight 444 flying from Chicago to Washington, D.C., fills with smoke after a bomb detonates in the luggage compartment. The plane lands safely, since the bomb did not work as intended. Several passengers suffer from smoke inhalation.

- June 10, 1980: United Airlines President Percy Woods is injured when he opened a package holding a bomb encased in a book called Ice Brothers by Sloan Wilson.

- October 8, 1981: A bomb wrapped in brown paper and tied with string is discovered in the hallway of a building at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. The bomb is safely detonated without causing injury.

- May 5, 1982: A bomb sent to the head of the computer science department at Vanderbilt University injures his secretary, after she opened it in his office.

- July 2, 1982: A package bomb left in the break room of Cory Hall at the University of California, Berkeley explodes and injures an engineering professor.

- May 15, 1985: Another bomb in Cory Hall at the University of California, Berkeley injures an engineering student.

- June 13, 1985: A suspicious package sent to Boeing Fabrication Division in Washington is safely detonated, but most of the forensic evidence was lost.

- November 15, 1985: A University of Michigan psychology professor and his assistant are injured when they opened a package containing a three-ring binder that had a bomb. The bomber included a letter asking the professor to review a student’s master thesis.

- December 11, 1985: A bomb left in the parking lot of a Sacramento computer store kills the store’s owner.

- February 20, 1987: Another bomb left in the parking lot of a Salt Lake City computer store severely injures the son of the store’s owner. A store employee sees the man leave the bomb, and that witness account helped a sketch artist create the composite sketch.

- June 22, 1993: A geneticist at the University of California is injured after opening a package that exploded in his kitchen.

- June 24, 1993: A prominent computer scientist from Yale University lost several fingers to a mailed bomb.

- December 19, 1994: An advertising executive is killed by a package bomb sent to his New Jersey home.

- April 24, 1995: A mailed bomb kills the president of the California Forestry Association in his Sacramento office.

“He was the most careful serial bomber anyone had ever seen.”

Kathleen Puckett, special agent (retired), UNABOM task force

Puckett pointed to very particular spellings and phrases—such as the British spelling of the word “analyse”—as unique identifiers in the text that she hoped would catch someone’s eye.

Sure enough, a few months after the manifesto was published, a lawyer representing David Kaczynski called the FBI. He provided them with a 23-page essay his client’s brother, Theodore Kaczynski, wrote in 1971. The agent who first read it immediately spotted similarities.

Turchie said that when he got a copy of the essay, the phrase “sphere of human freedom” jumped out at him. He said he went back to the Unabomber’s manifesto and found this line:

“We are going to argue that industrial-technological society cannot be reformed in such a way as to prevent it from progressively narrowing the sphere of human freedom.”

The similarities in the texts along with other evidence that came to light as agents investigated more of Kaczynski’s past and records made Turchie more and more certain that they had their man. “The little things started adding up,” he said. “Several of us believed we had identified the Unabomber.”

That was enough to get a search warrant for the rustic cabin in Montana where Kaczynski lived. Among the evidence found in the cabin were thousands of pages of Kaczynski’s handwritten notes, including confessions to all 16 bombings. His words helped agents find him, and they helped prosecutors build the case against him.