- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Media www.rajawalisiber.com – Analyzing the physical structures of refugee camps in Lebanon and Jordan sheds light on dynamics between the state, humanitarian organizations, and refugees.

Making a right turn next to a graffiti of Yasser Arafat on the wall, passing the blue dollar store, making another right after the huge water tank, a left by the lightbulb picture, a right after the Mecca graffiti, then going down the stairs—this was my routine every day for a month when I worked at mukhayyam—refugee camp—in Burj-El-Barajneh in the Southern suburbs of Beirut. On my daily walk I was constantly struck by how similar the camp felt to the Old Town (Bled el-Arbi) back home in Tunisia, with the buildings, cables, and dripping water holding the lives of an entire community. Particularly striking was the sense of solidarity this space and others like it appear to foster between its inhabitants.

While camps like Burj-El-Barajneh have merged into the urban architecture of the city over the years, contrasting the planning processes of the more recent Zaatari and Azraq camps in Jordan, these sites all demonstrate the tensions between the camps’ architects and inhabitants in their senses of what the architecture of a refugee camp should prioritize. As such, the physical structure of these camps provides a means to explore the power dynamics between refugees, humanitarian organizations, and the state apparatus at play.

What Is the Role of a Camp?

Refugee camps are the main context for the distribution of international assistance to refugees. However, despite their ostensibly temporary nature, these camps have also become the main long-term living environments for many refugees and, in the case of Palestine, future generations. Despite this reality, humanitarian organizations continue to center resource allocation and distribution of goods to these camps within a framework of emergency management and crisis resolution.

As humanitarian organizations remain active in these camps, the constant interaction between staff working in the mukhayyam and the camp’s residents shapes a particular power dynamic, turning refugees into clients awaiting their goods from organizations that possess the power to direct the flow of goods. This imbalance calls into question whether humanitarianism can be left untouched by neoliberalism, and how humanitarian organizations navigate the reality that prolonging economic dependence in the camps ensures the market for their goods and services.

Refugee camps are the UNHCR’s preferred choice for humanitarian intervention because they provide an environment in which aid can be easily delivered, distributed, and monitored (UNHCR, 214b). Thought to be temporary, camps are often isolated to remote areas with minimal interaction to the host state’s economy. Refugee camps therefore separate the ‘alien’ from the nation, initially obscuring refugee life within the folds of camps’ urban landscapes. Yet as millions of refugees remain in these structures for years on end, they rely heavily on aid organizations as the sole provider of relief, and their isolation serves as a barrier to intervention from other organizations. To combat this dependence, the UNHCR promotes a ‘self-reliance’ policy to enable social accountability and cohesion.

Yet international humanitarian organizations’ efforts are likewise often tainted by corrupt mediators and local initiatives that fail to distribute the resources and aid they receive. One Burj-Al-Barajneh resident, Mira, claimed when interviewed that humanitarian action in the mukhayyam is only “[partly] successful as a lot of the aid is taken by associations and committees responsible for the camp.” Often, beneficiaries do not receive the aid that has been allocated because of internal theft. Despite the difficulties, Farah, another resident, claims that she and other refugees do not oppose humanitarian organizations, but rather, “We appreciate the way [organizations] promote local initiatives and community organizers but we also want someone nadhif (clean, honest) to be able to help us with what we need,” she said.

The foundation of Jordan’s Zaatari camp—which has built a robust economic structure without the UNHCR’s ‘self-reliance policy,’ gives insight into an alternative model of refugee living that prioritizes residents’ spatial needs and economic inclinations. The camp opened in 2012 to temporarily “host” Syrian refugees fleeing the civil war, then in its second year, but has since transitioned into a permanent settlement.

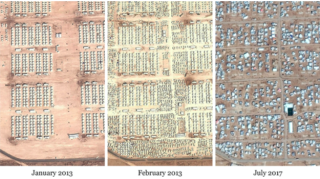

The refugees of Zaatari camp have established a thriving economic market that circulates approximately 10 million JDs per month (UNDP, 2012; UNHCR, 2015). This is in part attributed to a strong sense of community refugees have established within the camp. Zaataricamp is known for its experimental planning and its adaptive expanding size. Early images of the camp show rows of tents placed on a deserted land near small villages. However, the increasing numbers of refugees arriving to the camp exceeded the initial capacity of 15,000 persons (UNHCR, 2012b) resulting in an expansion of the camp outside of the planned order of the UNHCR and relief organizations, shown through satellite imagery below.

To regain control, UNHCR imposed humanitarian disciplinary planning. The camp was divided into districts demarcated by wide asphalt streets. The final master plan showed a planned area and an abstracted organic-like zone, with both parts designed to complement one another in relocating refugees and welcoming new ones. Yet this strategic plan collapsed against the changing dynamics within the camp. Instead, refugees moved their shelters around the camp in response to socio-cultural relations, settling between and inside the planned shelter units.

Figure: The spatial transformation in the Zaatari camp from disciplinary planning to informal urbanism (Source: Google Earth)

Residents also created markets, organized riots and demonstrations, and made use of available resources to organize the camp the way they saw fit. Eventually, an alternative spatial structure appeared at the Zaatari camp. Instead of being organized to maximize efficiency of the aid organizations, refugees restructured the camp over time to fulfil their daily needs.

The Zaatari camp became one of Jordan’s largest urban centers via refugees’ necessities and desires to lead a dignified life. The correlation between a sense of control over the space and economic independence also appears; refugees in Zaatari take part in economic activities including selling vouchers to buy goods directly from the refugees’ market and working for humanitarian organizations in garbage collection, construction, and teaching. For example, the Zaatari souk, which first appeared as a set of shacks, is now a thriving market that stretches for more than two kilometers. A UNHCR site planner noted that the market emerged along the asphalted streets, but the impetus for the market itself arose from the camp’s inhabitants. A shop owner commented that “people like to walk here, even if they do not want to buy. They keep coming and going all the time […].” demonstrating that the inhabitants have shaped public spaces in ways usually attributed to urban settings rather than temporary shelters.

In response to the decentralization of the Zaatari camps, the UNHCR, in conjunction with the Jordanian government, designed the Azraq camp to incorporate ‘lessons learned’ from Zaatari’s disorganization. Notably, Azraq’s design has decreased rather than increased the likely permanence of the camp. Rows of moveable white cabins built using steel rather than concrete are a clear indicator that the camp is not meant to last. The temporariness signals a degree of state control over the camp not seen in Zaatari—the camp can more easily be dismantled, and its inhabitants relocated, when the state sees fit.

Likewise, the Azraq camp’s planning incorporated lessons from what organizations perceived as the Zaatari camp’s difficulties and failures, manifesting in disciplinary planning to manage the camp and its population through strict spatial and shelter arrangements. Therefore, the solution that resulted from the lessons learned at Zaatari was an increase in policing structures aimed at refugee communities within the camp in an attempt to facilitate their management and control by humanitarian workers and service providers.

Nevertheless, Azraq remains a space where refugees have been able to reclaim some of their agency by negotiating margins of informality. Indeed, inhabitants of the camp were able to either dismantle parts of the empty shelters and use them to build parts of their homes or connect the empty spaces between the shelters in order to establish a bigger housing accommodation. These processes were enabled by interactions with police officers inside the camp who would force refugees to fix the alterations they made to their homes if they deemed them highly visible. However, this never stopped Azraq residents from changing the general structure of the camp the next day. In a sense, while the presence of these strict rules differentiate Azraq and Zaatari, breaking them provides a similarity that embodies the reappropriation of a communal space, thus making it less temporary in nature.

UNHCR describes taking a “village-based approach” to planning to “foster a greater sense of ownership and community among residents.” By organizing itself in this way, Azraq enabled control over its population and ensured that the police and the humanitarian organizations were fully in charge. This stands in contrast to Zaatari camp, which is partially governed by its residents. And yet, visitors to Azraq camp noted that Azraq suffered economically precisely because of this planning, as demonstrated by government delays in opening a market in Azraq and in providing work permits.

The urbanization of camps is increasingly organized with the notion of management and logistics in mind. This concept coupled with the increasing role aid organizations are playing in camp governance is called humanitarian urbanism. This type of governance implementation by humanitarian organizations is a complex issue due to the power imbalances inside the camps between organizations and refugees regarding resource distribution, social service provisions, and control of movement. The state of impermanence in which refugees live stands in contrast to the permanence of control humanitarian organizations exert over the camp populations. Even still, humanitarian urbanism remains the model used among most camps in the region.