Security issues won’t top Tunisia’s agenda in 2021, but the sheer volume of citizens mobilized into the jihadist milieu over the past decade suggests that the consequences will be felt for years to come.

- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3437

Media www.rajawalisiber.com On February 19, 2011, Tunisia announced a general prisoner amnesty following the overthrow of President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, in the process allowing 1,200 jihadists back onto the streets to organize. These individuals included 300 operatives who had previously fought in Afghanistan, Algeria, Iraq, Somalia, and Yemen.

In the ten years since then, the country’s jihadist movement has morphed through various phases and is now at its greatest lull since the revolution, at least in terms of terrorist attacks. The current situation mirrors the movement’s pre-revolution status in other ways as well, with most of its fighters located on foreign fronts, most of its attack planners based in the West, and members imprisoned in multiple countries. The main difference now is that the number of those involved is much larger. And despite the government’s major accomplishments against jihadists over the past five years, it still faces formidable challenges related to reforming its security sector, judiciary, prison system, and governance problems—any of which could undermine the country’s ability to prevent a resurgence of the acute security threats it met from 2011 to 2016.

Evolution Since the Revolution

Following the amnesty, released jihadists formalized what they had been planning in prison since 2006: the establishment of a new group called Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST). Due to the transitional government’s lack of legitimacy at the time, most authorities were focused on preparing the country for elections, so AST had ample space to operate without much oversight. This gave members a chance to link up with jihadists in Libya and protest for the rights of their fellow Tunisian fighters in Iraqi prisons, while at home they forcibly took over 400 mosques throughout the country and began harassing secular artists, activists, and politicians.

AST achieved even greater freedom of operation after the elections, which placed the Islamist party Ennahda atop the new parliament. Ennahda treated the group with a light touch based on its own experiences enduring crackdowns in previous decades. It also naively believed that AST could be coopted into the new democratic system—even though democracy is anathema to jihadist ideology. Consequently, AST was permitted to conduct more than 900 events in 2011-2013, including religious lectures, dawa (proselytizing) forums, and charitable caravans.

Yet even as the group claimed to favor a dawa-first approach, members unofficially engaged in hisba (moral policing) activities and supported a secret military wing that trained individuals in Libya. Following an attack on the U.S. embassy in 2012 and the assassination of leftist politicians in 2013, Ennahda began to crack down on AST’s activities amid pressure from the political opposition and concerns about its own standing. By August 2013, the government had designated the group as a terrorist organization.

One effect of the crackdown at home was to increase AST’s recruitment of fighters for deployment abroad. In total, around 3,000 Tunisians ended up going to Iraq and Syria, while up to 1,500 (including some returnees from Syria) went to Libya. Based on the experience they had accumulated with AST, Tunisians became key components inside al-Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra, and later within the dawa and administrative spheres of the Islamic State (IS). Some members also helped with planning, guidance, and training for IS external operations in Europe and Tunisia.

Indeed, Tunisia suffered several large-scale jihadist attacks beginning in 2015, including the Bardo Museum shooting in Tunis, the Sousse beach shooting, and the bombing of a Presidential Guard bus, along with smaller insurgent-style attacks in the mountains near the Algerian border, primarily in Kasserine governorate. The strengthening IS presence in Libya also gave jihadists another opportunity to break national borders as they had in Iraq and Syria. Yet Tunisian security forces and local resistance thwarted their 2016 attempt to capture Ben Gardane and link it up with Sabratha and other communities across the border in Libya.

In many ways, this was a turning point in the fight. Smarter counterinsurgency and law enforcement efforts enabled Tunisia to slowly degrade the jihadist movement, from targeting local al-Qaeda and IS-linked sleeper cells to addressing the low-boiling insurgencies in the mountains near the Algerian border. Since April 2019, the government has seen itself as being on the offensive instead of the defensive, actively preventing jihadists from reestablishing their capabilities as they did in varying ways from 2011 to 2016.

Situation in 2020, Outlook for 2021

Jihadist activity in the mountains near Algeria continued to degrade in 2020, and five more IS leaders were confirmed to be killed: Bassem Ghnimi, Mohamed Habib Hajji, Hafedh Rhimi, Nadhem Dhibi, and Muhammad Wanis bin Muhammad al-Haji. In all likelihood, little more than a dozen IS fighters are likely still holed up in the mountains. Yet Katibat Uqba ibn Nafi, the Tunisian affiliate of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), saw no leaders killed this past year, suggesting that around forty or so of its members are still active in the mountains. Then again, this affiliate has not claimed responsibility for an attack since April 2019, which suggests that either the group is smaller than the government’s past estimates, or its members are no longer able to connect with AQIM’s media network in Algeria.

Although COVID-19 has made it difficult to parse out the complete strength and attack risk of these and related groups, their pre-pandemic trajectories suggest that the drop in attacks could be a sign of broader weakness. The coming months will presumably provide greater insights as Tunisians get vaccinated and a semblance of normalcy returns.

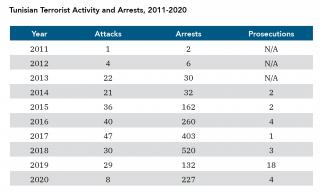

At the same time, however, jihadist-related arrest numbers have increased, and Tunisia’s Interior Ministry has offered little transparency on the specifics behind these detentions. Are these first-time offenders or individuals who have previously been arrested for jihadist activities?

In any event, the number of cases prosecuted—which at times includes multiple individuals—is down again. This is likely a result of the pandemic, but it might also stem from the troubling degradation of institutions that many Tunisians believe has been ongoing for several years, from eroding rule of law to the reversal of progress made during the revolution’s initial aftermath. Once the worst of the pandemic has receded, Washington should urge Tunisia’s Justice Ministry to try cases more swiftly, which could help restore faith in rule of law, bring more jihadist operatives to justice, and ensure the system does not get overburdened.

Another concern about this judicial record stems from a March 2020 report by the Tunisian Organization Against Torture, which documented persistent human rights violations in the country’s detention facilities. Here too, the U.S. State Department should step in, pushing Tunis to stop such practices given their negative effect on the government’s legitimacy at home and abroad.

As for the challenge of repatriating Tunisian citizens affiliated with IS and their families, there has been little progress on that front beyond the return of 6 children who had been held in Libya. Around 50 more children remain in Libya and 200 in Syria, with most of them born abroad. The number of Tunisian adults held in those two countries is unknown, however.

To be sure, security issues are unlikely to reach the forefront of Tunisia’s agenda in 2021 given the country’s bevy of other concerns, from the pandemic’s economic consequences to parliament’s continued instability and friction with President Kais Saied. Yet even as immediate security problems became more manageable in recent years, the sheer volume of Tunisians mobilized into the jihadist milieu over the past decade suggests that the consequences will be felt for years to come, as individuals complete their prison sentences, reorganize abroad, or are inspired to plan attacks locally. This is why the uiaforementioned reforms are crucial to address sooner rather than later. Past governance problems spurred many Tunisians to join the state-building projects offered by AST and IS, and continued lapses will give the jihadist movement fodder in the future—no matter how much it may have been weakened of late.

Aaron Zelin is the Richard Borow Fellow at The Washington Institute.